Leonardo da Vinci,

Portrait of Ginevra Benci.detail.1474

It takes two to speak the truth -

one to speak, and another to listen.

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862)

EuMuse: Sound, Music, and the Human Being Reconsidered

Most contemporary sound and music frameworks approach the human being through a narrow functional lens. In prevailing models, the listener is treated primarily as a nervous system to be regulated, a data-processing brain to be stimulated, or a symptom profile to be managed. While such perspectives have yielded partially measurable insights, they are insufficient to explain the depth, durability, and civilizational role of m u s i c across human history.

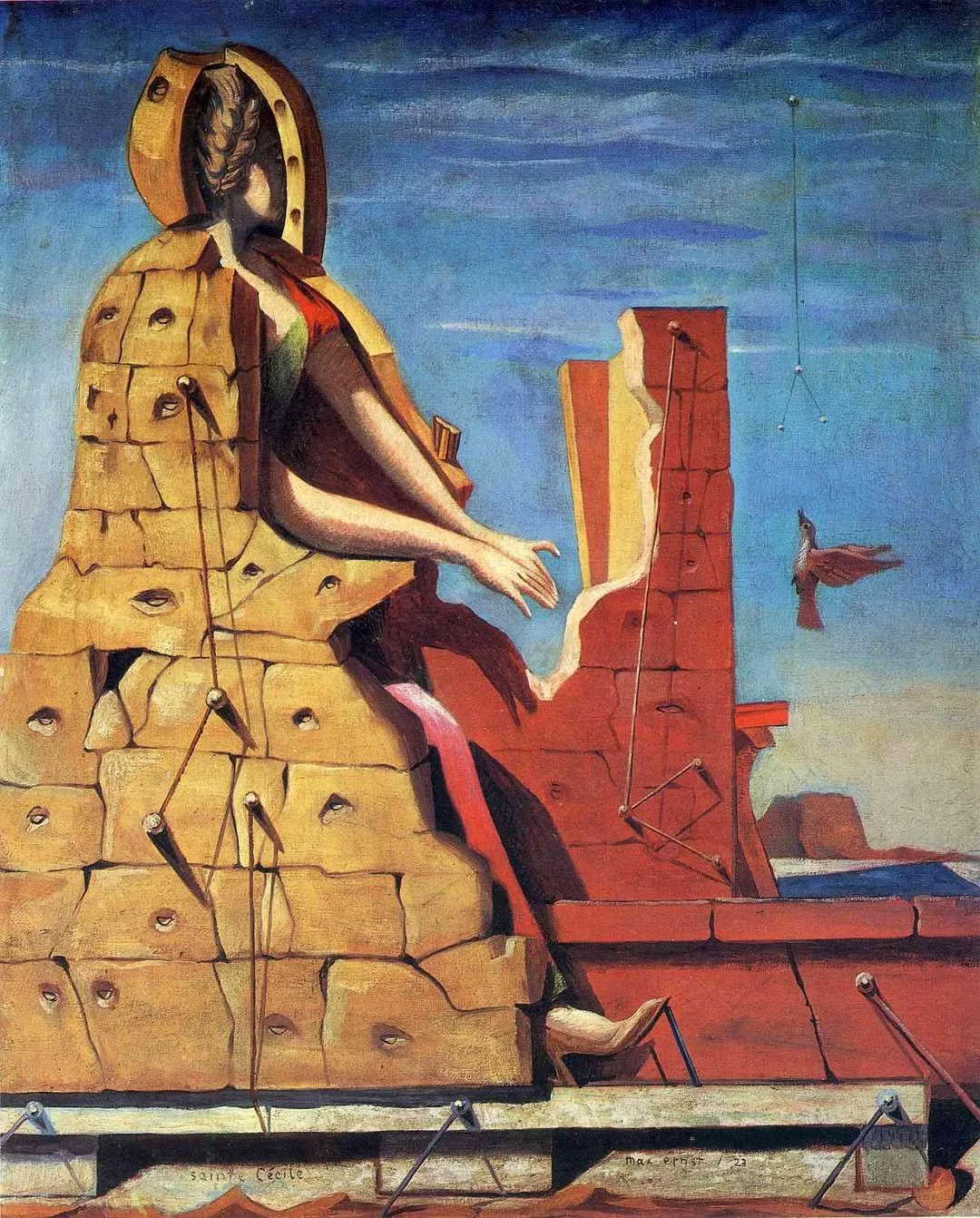

Max ernst

saint cecilia (invisible piano), 1923.

Time is the greatest innovator.

Francis Bacon (1561-1626), “Of Innovations”, 1625

Nevertheless, we should not fear change; on the contrary, we should accept responsibility for guiding it – i.e., learn how to incorporate new knowledge to advance and thrive. Creative reassembling, not certainty, is a key part of intelligence.

We still think of our senses – sight, hearing, touch – as purely reflecting the outside world. But they don’t. They provide us with a mixture of the world out there and our own expectations. Pure knowledge, the Pythagoreans argued, was the purification (catharsis) of the soul. This meant rising above the data of the human senses. Yet another beautiful example supporting the fact – of how important it is to be aware of the need to learn (and re-learn) how to listen.

EuMuse is based on a fundamentally different anthropological and scientific model. It understands the human being as a biological–aesthetic–ethical–educational unity, and it treats listening not as passive reception but as an active, learnable, and goal-directed human capacity. Within this framework, beauty, ethics, and education are not values added after technical optimization; they are conditions of efficacy.

Modern Renaissance minds of our time identify beauty, truth, and curiosity as the most consequential qualities for building safe and human-aligned artificial intelligence.

hendrick terbrughen

woman playing a lute, 1626.

Music is another planet.

Alphonse Daudet (1840-1897)

Beauty and Aesthetics as Scientific Variables

Across civilizations, beauty has never been understood as subjective decoration alone. It has been associated with proportion, balance, the interplay of symmetry and asymmetry, temporal coherence, and resonance with natural rhythms. These aesthetic principles recur in sacred architecture, ritual music, oral traditions, and pedagogical systems that endured for centuries or millennia.

Contemporary science is now rediscovering the functional relevance of these principles through disciplines such as neuroaesthetics, predictive processing neuroscience, affective neuroscience, and embodied cognition.

A key insight underlying EuMuse is that the nervous system relaxes, reorganizes, and learns more deeply in the presence of coherent, intelligible structure than in the presence of raw stimulation alone. Beauty, in this sense, functions as a regulatory signal.

Crucially, aesthetic quality directly determines biological outcome. Two sounds with nearly identical frequency spectra can produce very different physiological and psychological effects depending on their intentional structure, temporal phrasing, harmonic directionality, and use of silence and spacing. This is why ancient chant is not equivalent to background noise, why consciously, knowledgeably designed music cannot be reduced to playlists, and why algorithmically generated sound is not interchangeable with living acoustic intelligence.

Within EuMuse, this principle is explicit: aesthetic intelligence is biologically consequential.

Sound and Music: A Critical Distinction

EuMuse makes a clear and necessary distinction between sound and music.

Sound, in EuMuse terms, is a physical and biological phenomenon. It is vibration organized in time that directly interacts with the auditory system, the autonomic nervous system, respiration, posture, and internal rhythms. Sound can entrain physiology regardless of meaning or intention. Because it bypasses many conscious filters, sound is powerful—and ethically consequential.

Music, by contrast, is sound shaped by intentional structure, aesthetic intelligence, and cultural meaning. Music is not defined by genre or style, but by organization: proportion, temporal coherence, harmonic directionality, phrasing, silence, and resonance with embodied human rhythms. Music operates simultaneously on biological, cognitive, emotional, and symbolic levels.

EuMuse does not treat all sound as music, nor all music as biologically or ethically appropriate. This distinction is central. Undifferentiated sound can stimulate, distract, or overwhelm. Music, when aesthetically coherent and knowledgeably designed, can regulate, educate, and integrate.

Dosso Dossi

(1490-1542)

A personification of geometry

Experience does not ever err; it is only your judgment that errs in promising itself results which are not caused by your experiments.

Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1519)

Goal-Oriented Listening Modules: EuMuse in Practice

The practical expression of the EuMuse framework is the design of goal-oriented listening modules. These are not playlists or background soundscapes. They are carefully structured listening experiences designed to support specific biological, cognitive, or developmental goals—such as regulation, recovery, learning, or integration.

Each module integrates acoustics and physiology, aesthetic coherence, ethical constraints, educational intent, and often architectural or environmental resonance. Listening, in this context, becomes an intentional act rather than passive exposure.

Ethics: Music (and sound) as Responsibility, Not Content

Music is uniquely powerful because it bypasses many conscious filters. It entrains physiology, shapes emotional states, and influences development — particularly during prenatal life, infancy, and childhood. For this reason, any system that deploys sound intentionally and at scale is exercising a form of biological power.

EuMuse places ethics at the center of music science, aligning its approach with medical ethics, educational ethics, and architectural responsibility. Ethical considerations are not external constraints; they are intrinsic to the design of effective music-based interventions.

Jan van Eyck

A man in turban,1433

Once a word has been allowed to escape, it cannot be recalled.

Horace (Quintus Horatius Flaccus) (65 BCE – 8 BC)

Education: Listening as a Learned Human Capacity

Historically, listening was cultivated as a foundational human skill. Chant, rhetoric, liturgy, apprenticeship, and oral transmission all trained attention, memory, and silence. Listening was slow, deliberate, and integrated into communal life. In contrast, modern culture fragments auditory attention, replaces listening with consumption, and accelerates sound beyond the nervous system’s capacity to integrate it.

EuMuse reclaims listening as a form of education, not therapy alone. It treats listening as a learned capacity that shapes how individuals think, feel, and relate to the world. This perspective is supported by developmental neuroscience, pre-instrumental music pedagogy, attention science, memory formation research, and studies of intergenerational transmission. Its integrated axes include aesthetic intelligence understood as coherence, listening education and development, and architectural and environmental resonance. Why this matters: Without beauty, sound becomes mere stimulation. Without ethics, sound becomes manipulation.

Civilizations that cultivated listening cultivated continuity.

My focus remains on mankind's need to k n o w - to know what is out there. And “as to science itself, it can only grow …” (Galileo, Dialogue, 1632)

Marina de Moses